What You Need to Know about Emotional Regulation

You’re supposed to have met your friends for lunch five minutes ago. However, you’ve spent the last ten minutes stalking the parking lot trying to find a parking spot. Suddenly, you notice someone starting to pull out of a space – finally! To make things even better, it’s right up front, the perfect location. You stop and put on your turn signal to let people around you know you’re waiting. Just as you’re about to turn in, someone swings in from the other side and steals your spot. What do you do? Do you honk the horn? Scream? Curse? Do you stay calm and continue searching for a new spot? If you stay calm even when you were frustrated and annoyed, you regulated your emotions ;-).

Emotional regulation is the ability to influence and change how we respond to an emotion. Would your response to the parking space be different if you were by yourself versus if kids were in the car? What if you were driving your boss to a meeting? How we respond to and express our emotions changes based on our environment and the people that are around. This ability to change and alter our response is ‘emotional regulation’.

Why Do we Care About Emotional Regulation?

The ability to regulate emotions relates to social language and communication. In the preschool classroom, young children spend their time playing in groups. While building creations in blocks center, children are expected to regulate their emotions so that when upsetting or frustrating things happen, they can problem solve in a safe fashion.

Children who show strong emotional responses are at increased risk for receiving ‘consequences’ from their teachers (ex: being removed from a play area of the classroom). Research suggests that a child’s ability to regulate their emotions at 3-4 years of age predicts their social relationship and engagement (Denham et al. 2003). Children who experience more ‘outbursts’ or show higher levels of anger experience increased difficulty playing and engaging with peers.

How Does Emotional Regulation Develop?

The idea that young children are expected to regulate their emotional state seems a little far-fetched. I would argue that expecting a child to independently regulate their own emotions is often unreasonable – particularly when thinking of certain temperaments and personalities. The ability to regulate your emotions is complicated and many adults find themselves struggling with this task. Children don’t *choose* to be unable to regulate their emotions – no one *chooses* to actively have challenging days and to experience out of control responses. Instead, when children experience difficulty with emotional regulation, that’s telling us they are struggling to develop the skills that are needed to effectively self-regulate.

To understand what would be ‘reasonable’ from a developmental standpoint we have to have a grasp on how emotional regulation and related skills develop.

| Two years old: | Able to stop actions to follow simple rules but still require a high level of adult support for regulation. |

|---|---|

| Three years old: | Can share the rules or expectations for a situation but may not yet be able to consistently do the expected actions. |

| Four years old: | Developing additional Theory of Mind abilities which assists with stopping and changing tasks/engaging in expected actions. |

| 4;6 - 5 years old: | Increased success independently regulating |

*adapted from Howland, 2014

You can see that the preschool years can be a challenging area for all children – particularly those who struggle with emotional regulation and the ability to change their actions/responses to situations. To make things even more complicated, around the age of three, children are able to state the expected actions (or the ‘rules’ for a situation) but still may experience difficulty doing the action or following the rule. This is *such* an important point to consider. All too often, adults assume that because children can tell you a rule or an expectation that means they’re capable of following the rule or expectation. That’s just not the case. Knowing the expectations and having the skills to *do* the expectation in the moment are very different things. For children who are experiencing delays in this area, they may still experience this exact same challenge at four or five years of age. When parents, teachers, or caregivers interpret the ability to share a rule as an ability to follow the rule, they’re doing a large disservice to the child.

What can we do to support emotional regulation?

Difficulty with emotional regulation can result in difficulty engaging in social interactions and play. And unfortunately, other adults and teachers often perceive children who struggle with emotional regulation negatively (Denham et al. 2003). Clearly this viewpoint is not helpful. Much of this perception stems from a misunderstanding of what is actually going on. Remember, children develop the skill to tell you the rules and expectations *before* they develop the ability to actually engage in those actions. Education is the key to changing the perspectives of others (family members, teachers, caregivers).

It's so vital for grown-ups in these situations to keep their own perspectives in check. Are you perceiving the child as being ‘spoiled’ or ‘intentionally disobedient’? Are you perceiving the child as having a hard time and struggling to regulate their body? How we perceive the situation changes how we respond to it.

“We don’t expect a child to run before they walk so we can’t expect a child to self-regulate if they can’t regulate with assistance.”

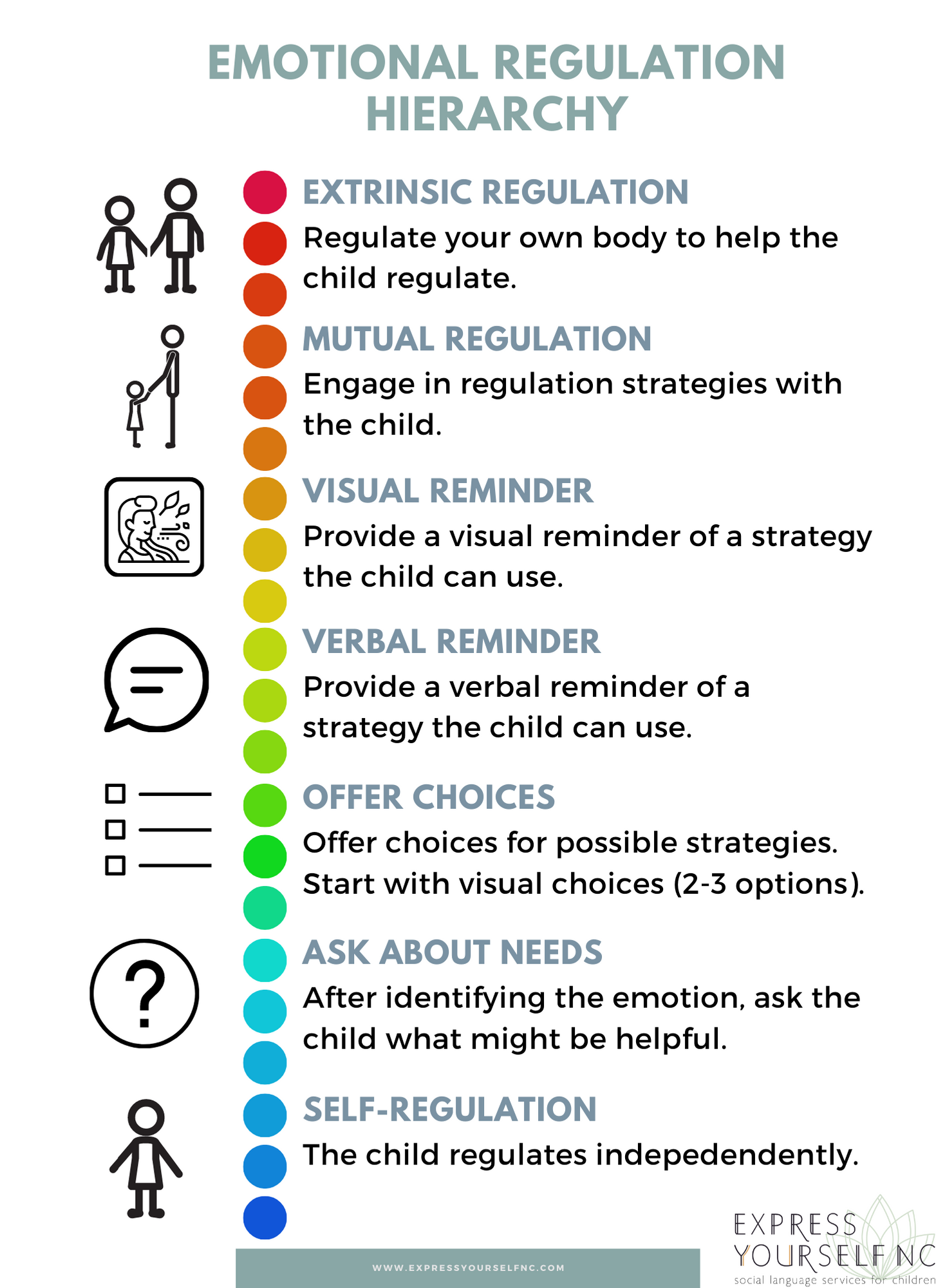

Because emotional regulation follows a developmental hierarchy from external regulation (someone else regulating their body to help the child) to self-regulation, it is often helpful to consider where on this journey a child’s skills fall. Yes, these skills have developmental milestones. However, that doesn’t mean that everyone meets those milestones at the same time. We don’t expect a child to run before they walk so we can’t expect a child to self-regulate if they can’t regulate with assistance.

While working with children to develop emotional regulation, I’ve developed this general hierarchy to support children from moving from extrinsic regulation to self-regulation. I’ve also put all this information in a color coded handout for easier access. Access your printable emotional regulation hierarchy handout.

Extrinsic regulation

During extrinsic regulation, a child relies on an adult to regulate for them. This is done by the adult regulating their own body. The child doesn’t do anything else and isn’t expected to do anything else. Extrinsic regulation is so often overlooked. For that exact reason, it has its very own blog post to really dive deep into this concept. Check out How to Help your Child when they 'Refuse' Strategies for more goodies on extrinsic regulation.

What this looks like for calming: The adult engages in regulating strategies without *any* demands on the child. This means that the adult is taking nice, deep, breaths. The adult is modeling slow movement, talking in a calm tone, and using a slower rate of speech. Extrinsic regulation can be incredibly powerful and oh so helpful for when a child just isn’t able to actively *do* anything in the moment. If you haven’t already, give the extrinsic emotional regulation blog a read.

Mutual engagement in regulation strategies

Mutual regulation occurs when an adult and child engage in regulation strategies together. The strategies being used have already been discussed, practiced, and mutually decided upon and are familiar to the child.

What this looks like for calm: taking five deep belly breaths together, visiting the cozy corner together, exploring sensory bottles etc. The key is that the adult is doing the activities with the child – serving as a model for how to do the exercises and also adding in some extrinsic support for regulation. It’s not uncommon for adults to start at the extrinsic regulation level and as the child begins to regulate (from the regulation being provided by the adult), the child then joins the adult in using the strategies.

Visual reminders for strategies

It can be hard to remember to use strategies. At this level, the adult provides a visual reminder for possible strategies that might be helpful. For this strategy to be successful, the visual message *must* be provided before the child is experiencing incredibly strong or intense emotions.

What this looks like for calming: Showing a child a picture for a breathing strategy or for the ‘safe space’. Providing a video model of the child moving to the ‘safe space’. It’s not uncommon for this stage to be paired with mutual engagement of strategies and also some extrinsic regulation.

Specific verbal reminders

Verbal comments can be challenging. For some children, stating something that may be helpful can be perceived as an additional ‘demand’ and can send the child into overload. Therefore, when initially using verbal reminders they should be used with caution and only be used when you’re noticing the beginning stages of emotional escalation. At this level, an adult provides the child with a specific reminder of what strategies might be helpful for that child based on the emotional and sensory needs the adult is noticing.

What this looks like for calming: “I see your hands are in fists and your face looks red. It seems like your body could use some deep breaths”. “Try taking some long, deep, breaths”. “Let’s try some hand presses or belly breathing”. “Your body seems frustrated, the cozy corner might help you stay in control”. Verbal statements can be hard to process and receive - particularly in the moment. With that in mind, it’s possible that some children will skip this stage - moving directly from visual reminders to being provided with visual choices.Offer choices for strategies

When a child is ready to move towards more independent identification of strategies, choices are a great starting point. At this level, adults offer the child a choice of previously identified and practiced strategies to choose from. Use the visuals from the visual reminder level. If a child has multiple options for an emotional state, start by offering 2-3 choices at a time. As a child becomes more comfortable choosing from options, increase the number of options available. Generally speaking, most children find that visual choices provide more assistance than verbal choices.

What this looks like for calming: “I see your body is moving quickly and your voice is sounding loud. You seem very excited. What could we try to help our body calm?” - show an array of three pictures (ex: deep breaths, jumping jacks, tight squeezes).Independent identification of needs

Once a child reaches this level, adults are still providing some insights to help a child notice and recognize how they might be feeling ‘in the moment’. However, once the emotional state has been identified, the child takes over the role of determining what they need next. When working at this stage, if a child isn’t sure what to do next, the adult can still add back in some choice support (either verbal or visual) to help the child generate some ideas. The act of an adult beginning to offer choices can help the child remember other options.

What this looks like for calming: “Your muscles look tight. You seem to be feeling angry. What do you think could help?”. If a child doesn’t respond or isn’t sure, offer some choices verbally, visually, or both – “Would you like some tight squeezes or to visit the cozy corner?”.Self-regulation

At this stage, a child is able to self-identify the sensations they notice within their body and they understand what that tells them about their emotional state (for more information for how sensations relate to emotions, check out our sensations blog). Once a child has identified their emotional state, they are confident in their ability to identify and perform an action that will help them to regulate their body to their current needs. Seem like a lot of steps and things to consider? That’s because it is ;-). Self-regulation is incredibly challenging. The development of this skill requires a high level of practice, patience, and support.

What this looks like for calming: A child starts to begin feeling a strong emotion, they notice the emotion and choose an appropriate strategy to help them stay in control.

While this hierarchy is designed to help guide your thinking for how to provide support and some of the different types of support that may be helpful, the specific examples given are for if a child is working towards calming their body. These examples were chosen because most often, parents and teachers ask for support and suggestions for how to help children who experience intense feelings of anger and frustration. However, it’s important to keep in mind that we don’t only regulate our emotions feeling mad or upset. We can also regulate ourselves to give us more energy when needed/wanted based on a situation. The end goal of emotional regulation is not always for a child to be feeling calm.

It’s also important to keep in mind that a child’s ability to regulate is constantly changing. While skills are developing, a child might be at the level of ‘visual support’ one day and ‘extrinsic regulation’ the next. Remember, a child’s ability to regulate their emotions depends on many factors. Some instances and experiences are more challenging to handle than others. A person’s ability to regulate also depends heavily on what else has happened in their day – have they experienced many frustrating situations? Are they tired? Are they hungry? (‘hanger’ is a real!).

When working to promote and support emotional regulation, consider what level of support your child is currently receiving - does it seem to be working? If yes - fantastic! If not, try adjusting to another level and re-evaluating. Emotional regulation is a skill. Children develop skills when adults provide the support and information the child needs. Repeatedly expecting a child to self-regulate when they don’t have the skills to do so is just going to result in frustration for all involved. Meet the child at their current skill level and work from there :-).

Citations:

Carlson, S. M., & Moses, L. J. (2001). Individual differences in inhibitory control and children’s theory of mind. Child Development, 72(4), 1032-1053.

Denham, S. A., Blair, K. A., DeMulder, E., Levitas, J., Sawyer, K., Auerbach-Major, S., & Queenan, P. (2003). Preschool emotional competence: Pathway to social competence? Child Development, 74, 238-256.

Howland, K. (2014). Developing executive control skills in preschool children with language impairment. Perspectives on Language Learning and Education, 21(2), 51-60. doi.org/10.1044/lle21.2.51

Kopp, C. B., (1982). Antecedents of self-regulation: A developmental perspective. Developmental Psychology, 18(2), 199-214.